Lecture 1: Polymorphism

Presenter Notes

Parametric Polymorphism

Parametric polymorphism is a pattern in which polymorphic functions are written without mention of any specific type, and can thus apply a single abstract implementation to any number of types in a transparent way.

Presenter Notes

Monomorphic methods can only be applied to arguments of the fixed types specified in their signatures (and their subtypes, we’ll see in a moment).

Polymorphic methods can be applied to arguments of any types which correspond to acceptable choices for their type parameters.

Presenter Notes

def slength(s: String): Int = s.length

slength("foo")

//res0: Int = 3

def length[T](l: List[T]): Int = l.length

length(List(1, 2, 3))

//res1: Int = 3

length(List("foo", "bar", "baz"))

//res2: Int = 3

Presenter Notes

We can mix in parametric polymorphism at the trait level, as well as add upper and lower type bounds:

trait Plus[A] { def plus(a2: A): A }

def plus[A <: Plus[A]](a1: A, a2: A): A = a1.plus(a2)

Presenter Notes

It's also interesting to compare the syntax with Haskell:

length :: Foldable t => t a -> Int

length = foldl' (\c _ -> c+1) 0

Presenter Notes

These implementations, along with Java generics, have quite a lot in common.

In fact one of the original designers of Haskell, Philip Wadler, was later one of the main architects (along with Martin Odersky, creator of Scala) in the development of Java generics.

Presenter Notes

Subtype Polymorphism

Scala is both an object-oriented and a functional programming language, so it exhibits subtype polymorphism as well as parametric polymorphism.

The methods that we’ve been calling monomorphic are only monomorphic in the sense of parametric polymorphism, and they can in fact be polymorphic in the traditional object-oriented way.

Presenter Notes

For example:

trait Base { def foo: Int }

class Derived1 extends Base { def foo = 1 }

class Derived2 extends Base { def foo = 2 }

def subtypePolymorphic(b: Base) = b.foo

subtypePolymorphic(new Derived1)

//res3: Int = 1

subtypePolymorphic(new Derived2)

//res4: Int = 2

Presenter Notes

Here the method subtypePolymorphic has no type parameters, so it’s parametrically monomorphic.

Nevertheless, it can be applied to values of more than one type as long as those types stand in a subtype relationship to the fixed Base type which is specified in the method signature.

Presenter Notes

Variance

In Scala, parametric and subtype polymorphism are unified by the concept of variance.

Variance refers to a categorical framework undergirding the type system (entirely separate from and in addition to the one commonly used in Haskell).

Presenter Notes

Presenter Notes

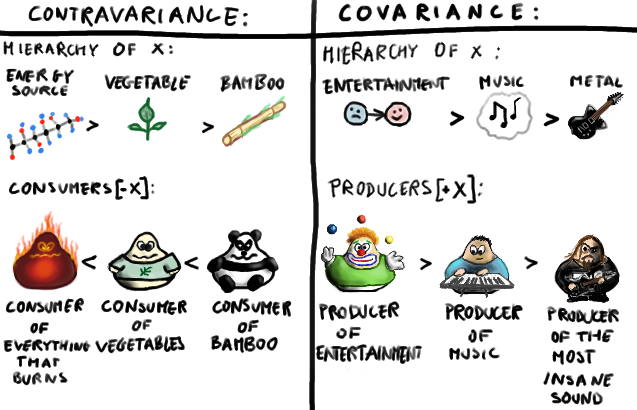

A type can be covariant when it does not call methods on the type that it is generic over. If the type needs to call methods on generic objects that are passed into it , it cannot be covariant.

A type can be contravariant when it does call methods on the type that it is generic over. If the type needs to return values of the type it is generic over, it cannot be contravariant.

Presenter Notes

Strongly typed functional languages like Scala and Haskell have function types.

For example: "a function expecting a Cat and returning an Animal" (written Cat => Animal or Function1[Cat, Animal] in Scala syntax).

Presenter Notes

The canonical example is the simple function of a single parameter:

trait Function1[-T1,+R] {

def apply(v1: T1): R

}

Presenter Notes

Being an OO language, Scala has sub-typing as well, so you elect to specify when one function type is a subtype of another.

In particular, Cat <: Animal implies:

Function1[Animal, Double] <: Function1[Cat, Double]Function1[Double, Cat] <: Function1[Double, Animal]

Presenter Notes

In general it is safe to substitute a function f for a function g if f accepts a more general type of arguments and returns a more specific type than g.

For example, a function of type Cat=>Cat can safely be used wherever a Cat=>Animal was expected, and likewise a function of type Animal=>Animal can be used wherever a Cat=>Animal was expected.

Presenter Notes

One can compare this to the robustness principle of communication:

"be liberal in what you accept and conservative in what you produce".

Presenter Notes

Rest assured that the Scala compiler will complain if you violate these rules:

trait T[+A] { def consumeA(a: A) = ??? }

// error: covariant type A occurs in contravariant position

trait T[-A] { def provideA: A = ??? }

// error: contravariant type A occurs in covariant position

Presenter Notes

Exercise

class GrandParent // Parent <: GrandParent

class Parent extends GrandParent // Child <: Parent

class Child extends Parent // Child <: Grandparent

class Covariant[+A]

class Contravariant[-A]

Presenter Notes

def foo(x: Covariant[Parent]): Covariant[Parent] = x

def bar(x: Contravariant[Parent]): Contravariant[Parent] = x

foo(new Covariant[Child])

//???

foo(new Covariant[GrandParent])

//???

bar(new Contravariant[Child])

//???

bar(new Contravariant[GrandParent])

//???

Presenter Notes

Presenter Notes

Ad-hoc Polymorphism

Ad-hoc polymorphism refers to when a value is able to adopt any one of several types because it, or a value it uses, has been given a separate definition for each of those types.

The term ad hoc in this context is not intended to be pejorative; it refers to the fact that this type of polymorphism is not a fundamental feature of the type sytem.

Presenter Notes

For example, the + operator essentially does something entirely different when applied to floating-point values as compared to when applied to integers.

Most languages support at least some ad-hoc polymorphism, but in some languages (like C) it is restricted to only built-in functions and types.

Presenter Notes

Other languages (like C++) allow programmers to provide their own overloading, supplying multiple definitions of a single function, to be disambiguated by the types of the arguments.

Ad-hoc polymorphism in Scala (with a large debt to Haskell) is most closely associated with what is known as the type class pattern.

Presenter Notes

Type classes define a set of contracts that the client type needs to implement.

Type classes are commonly misinterpreted as being synonymous with interfaces in Java or other programming languages.

Presenter Notes

The focus with interfaces is on subtype polymorphism.

However with type classes the focus is on parametric polymorphism: you implement the contracts that the type class publishes across unrelated types.

A second crucial distinction between type classes and interfaces is that for class to be a "member" of an interface it must declare so at the site of its own definition.

Presenter Notes

By contrast, any type can be added to a type class at any time, provided you can provide the required definitions, and so the members of a type class at any given time are dependent on the current scope.

Type classes are similar to the GoF adapter pattern, but are generally cleaner and more extensible.

Presenter Notes

There are three important components to the type class pattern: the type class itself, instances for particular types, and the interface methods that we expose to users.

The instances of a type class provide implementations for the types we care about, including standard Scala types and types from our domain model.

Presenter Notes

The type class itself is a generic type that represents the functionality we want to implement:

trait Show[A] {

def format(value: A): String

}

Presenter Notes

We define instances by creating concrete implementations of the type class and tagging them with the implicit keyword:

object ShowInstances {

implicit val stringPrintable = new Show[String] {

def format(input: String) = "show: " ++ input }

implicit val intPrintable = new Show[Int] {

def format(input: Int) = "show: " ++ input.toString

}

}

Presenter Notes

Instances are then exposed to users through interface methods.

Interfaces to type classes are generic methods that accept instances of the type class as implicit parameters.

There are two common ways of specifying an interface: Interface Objects and Interface Syntax.

Presenter Notes

Interface Objects

The simplest way of creating an interface is to place the interface methods in a singleton object.

object Printer {

def format[A](input: A)

(implicit printer: Show[A]): String = {

printer.format(input)

}

def print[A](input: A)(implicit printer: Show[A]): Unit = {

println(format(input))

}

}

Presenter Notes

To use the interface, we bring the relevant type class instances into scope and call the relevant method:

import ShowInstances._

Printer.print("foo")

//show: foo

Printer.print(42)

//show: 42

Presenter Notes

Interface Syntax

Another approach is to use type enrichment to extend existing types with interface methods.

Typelevel libraries often refer to this as “syntax” for the type class:

object ShowSyntax {

implicit class ShowOps[A](value: A) {

def format(implicit printer: Show[A]): String = {

printer.format(value)

}

def print(implicit printer: Show[A]): Unit = {

println(printer.format(value))

}

}

}

Presenter Notes

We use interface syntax by importing it along-side the instances for the types we need:

import ShowSyntax._

"foo".print

//show: foo

42.print

//show: 42

Presenter Notes

Example: Eq Typeclass

import cats.Eq

import cats.syntax.eq._

case class Point(x: Double, y: Double)

Presenter Notes

We define our instance of Eq[Point] in the companion object, and bring the Eq instance for Double into scope for the implementation:

object Point {

implicit val pointEqual = Eq.instance[Point] {

(point1, point2) =>

import cats.std.double._

(point1.x == point2.y ) &&

(point1.y == point2.y )

}

}

Presenter Notes

Now we can use our Eq typeclass implementation for Point to test different points for equality:

val p1 = Point(1.0,0.0)

val p2 = Point(1.0,0.0)

val p3 = Point(0.0,1.0)

p1 == p2

//res0: Boolean = true

p1 != p3

//res1: Boolean = true

Presenter Notes

Again, it's interesting to compare this to typeclass syntax in Haskell:

class Eq a where

(==) :: a -> a -> Bool

instance Eq Float where

x == y = x `floatEq` y

Presenter Notes

Note that one place where Haskell is much less verbose than Scala in the above implementation is the instance definition of the type class.

But here the added verbosity in Scala is not without a purpose and offers a definite advantage over the corresponding Haskell definition.

In Scala's case we name the instance explicitly, while the instance is unnamed in case of Haskell.

Presenter Notes

Because the instance is explicitly named in Scala, you can inject another instance into the scope and it will be picked up for use for the implicit.

So, for example, you could easily define, in different scopes, two or more different implementations of the same type class for the same type.

Presenter Notes

The Haskell compiler looks into the dictionary on the global namespace for a qualifying instance to be picked up.

In Scala's case implicits allow the compiler to do type-directed resolution of an argument locally in the scope of the method call that triggered it.

Presenter Notes

So the type class pattern is truly ad-hoc in the sense that:

- we can provide separate implementations for different types

- we can provide implementations for types without write access to their source code

- the implementations can be enabled or disabled in different scopes

Presenter Notes

Homework

Read Chapter 10 and get started on Chapter 11 in Functional Programming in Scala.